The Michigan State Numismatic Society

CREATING A LOCAL CURRENCY Michael E. Marotta

CREATING A LOCAL CURRENCY

Michael E. Marotta (MSNS 7935)

A local currency provides an economic “cul-de-sac” that keeps wealth within a community. Local money tends to stay close to home. This means that profits do not get exported via chain stores and multinational corporations. Instead, people buy and sell goods and services among themselves, with the currency being an accounting tool. About 30 towns have tried the experiment, some with more success than others. Ithaca, New York, launched its “Time Dollars” in 1991 and the program continues today.

In the late summer of 2003, I head a radio interview on WIAA-FM, Interlochen, in which two Traverse City community activists explained their plans for a hometown money. They sounded competent and intelligent and the project was compelling to me as a numismatist. I tracked them down by asking around at the Oryana Natural Food Co-op. I found Natasha Lapinsky and Chris Grobbel at Ball Environmental Associates. Lapinksi holds master’s in terrestrial biology from NMU. Grobbel earned a doctorate in community development at MSU. I interviewed them (and others) for an article that ran in the November 13, 2003 issue of Northern Express. I wrote a follow-up article for the June 10, 2004 issue.

Designing “Bay Bucks”

Lapinski and Grobbel told me that during the Great Depression, Traverse City had its own local currency, but that they had never seen one, only heard about this. So, I visited Coins & Collectibles on State Street, and talked to the guys. Richard Bond lent me samples of each of the two “Roosevelt” notes created in 1933. David Croad came up with an array of local tokens. From the ANA, I borrowed the Mitchell & Shafer catalog and the Curto monograph. I rejoined Mich-TAMS, and Paul Manderscheid of Liberty Coins in Lansing mailed me a sheaf of materials including his own notes updating Cunningham’s catalog.

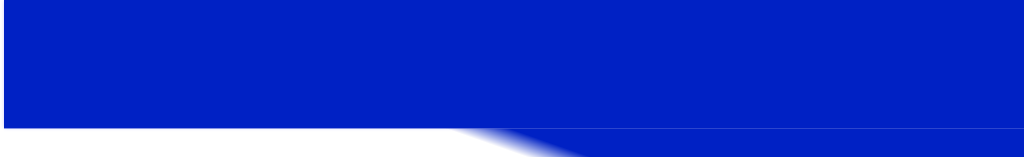

I began attending regular meetings of the Traverse Area Community Currency Initiative. It was pretty clear that most of the organizers and activists who were emotionally invested in the success of the project had little direct experience with money. I suggested that we could all sit down with crayons, pencils, or laptops and come up with a few design proposals to start with. In the silence that followed that, I passed out samples I had created in Microsoft Word. Cutting and pasting Danish and Vietnamese notes, I added security features and other touches. The committee responded favorably to the wildlife-and-agriculture theme. I pointed out that the work really needed to be done by accomplished designers with appropriate tools.

I began attending regular meetings of the Traverse Area Community Currency Initiative. It was pretty clear that most of the organizers and activists who were emotionally invested in the success of the project had little direct experience with money. I suggested that we could all sit down with crayons, pencils, or laptops and come up with a few design proposals to start with. In the silence that followed that, I passed out samples I had created in Microsoft Word. Cutting and pasting Danish and Vietnamese notes, I added security features and other touches. The committee responded favorably to the wildlife-and-agriculture theme. I pointed out that the work really needed to be done by accomplished designers with appropriate tools.

The general committee then allowed me to chair the design subcommittee. One of the project affiliates on the email list forwarded the name of a professor in visual communication at Northwestern Michigan College, Caroline Schaefer. She provided three students. For them, this was a class project and they ran it as a simulation of their intended careers. They developed a name and logo for themselves and we all signed off on a Statement of Work. I gave them samples of world currencies, a copy of Standish’s The Art of Money and links to websites for the International Banknote Society and the Paper Money Collectors. They dove into their work.

Starting on January 21, 2004, we met every other week and eventually every week. Brendan O’Brien, Pauline Viall, and Thomas Loomis (OVL Design) came up with several proposals, each a consistent series of wildlife, nature, farm, and ecology images. We discussed the pros and cons of features, formats, and other details. These were taken to the TACCI general committee once a month for review, comments, criticisms and suggestions. Basically, everyone was very impressed with the work.

Several factors motivated me to find letterpress printers for the production. First, there is the low–tech/high-touch component of an appropriate technology. Old-fashioned printing just feels right. It has texture and it carries a patina of craftsmanship that may not always be apparent in every detail but which is subconsciously undeniable. Also, in early 2003 while working in private security, I earned a certificate in computer crime investigation. Part of that education touched on counterfeiting. Letterpress work allows security features that are not so easy to photocopy. I found two local printers, both active in, or aware of, the alternative community, its orientations and other needs.

During this process of committee meetings and e-mailings, the local money medium came to be called “Bay Bucks.”

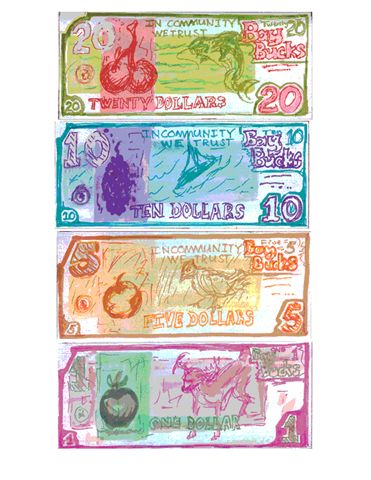

Four notes make up the series: BB1, BB5, BB10 and BB20. Each represents an eco-system: Dunes (Dune Lily and Piping Plover); Wetland (Morrell Mushroom and Ringtail Raccoon); Farm (Cherry Blossom and Barn Owl); and Forest (Lady Slipper and Whitetail Deer). The Petoskey Stone pattern supplied the border of all four faces. In addition, the upper left of the faces are die-cut around the denomination numeral. This allows easy identification of a Bay Buck by touch. Each note has its own motto: “Regional Community Currency” (BB1); “Traverse Area Community Currency” (BB5); “Bread for Your Watershed” (BB10); and “In Community We Trust” (BB20).

“In Community We Trust” is an obvious play on the Federal motto. The communitarian credo appears on other local money and was “In Ithaca We Trust” on the first of the modern scrips. The idea behind “Bread for Your Watershed” is that the geographical features of northwestern lower Michigan define both the flow of water and the movement of labor and capital toward the shorelines.

In Community We Trust

Ayn Rand said that gold is only a claim on the productive work of others. If nothing is produced, then even gold is worthless. (To Rand, it was important that gold be understood as an “objective” value, but never as an “intrinsic” value.) The success of a community currency depends completely on the number and kinds of people who will accept it. That acceptance must have high visibility.

Lapinsky, Grobbel, and the other activists identified about 100 local businesses that could benefit from participating in “Bay Bucks.” About 30 of them were considered early adopters. Leading that smaller set is the Oryana Natural Food Co-op.

Over 20 years old, Oryana now turns about $3 million a year in business. They have about 20 employees, both full time and part-time. They buy local farm produce. The store’s general manager, Bob Struthers, is enthusiastic about the potentials that a local currency offers. As a result, Oryana’s participation is central to the success of Bay Bucks. Even before the currency was printed, the Oryana newsletter announced that they accept the new money.

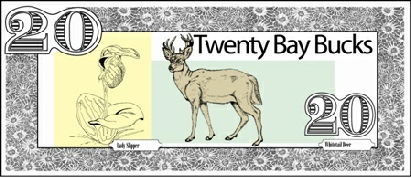

Among the other retailers are bookstores, groceries, healthcare, crafters, and restaurants. To advertise the hometown scrip, the TACCI committee commissioned a logo from. Patty Fabian, of Peninsula Partners. The logo will be used in “We Accept Bay Bucks” window signs as well as bumper stickers and print advertising. This logo also appears on the Bay Bucks notes.

The TACCI committee also commissioned two three-fold brochures to explain what a community currency is and how it works . Avoiding long paragraphs of political rhetoric, the handouts deliver short, declarative sentences, a list of websites and other resources.

. Avoiding long paragraphs of political rhetoric, the handouts deliver short, declarative sentences, a list of websites and other resources.

The Neahtawanta Research and Education Center agreed to host the community currency website. On that site is a FAQ, a list of Frequently Asked Questions, that delivers more details. Neahtwanta’s interest in community currency goes back at least to 1998 when they received a $10,500 grant from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation to study “com-munity sustainability.” That proposal included the study of how a localized scrip could work. Like Oryana, Neahtawanta has high visibility in Traverse City for their efforts with multinational non-government organizations. Neahtawanta also hosts the local events of the annual “Bioneers” conferences. Their primary business is a bed-and-breakfast on the Old Mission Peninsula.

In order to formalize the community currency initiative, TACCI hired a lawyer to draw up incorporation papers. As a not-for-profit entity, the Traverse Area Community Currency Corporation has the all the rights and responsibilities of an artificial and eternal individual under Michigan law. Staffing the board of directors will allow the committee to offer opportunities to lawyers, accountants, and others from the wider business community.

In order to formalize the community currency initiative, TACCI hired a lawyer to draw up incorporation papers. As a not-for-profit entity, the Traverse Area Community Currency Corporation has the all the rights and responsibilities of an artificial and eternal individual under Michigan law. Staffing the board of directors will allow the committee to offer opportunities to lawyers, accountants, and others from the wider business community.

Alternative Currencies

Community currency does not have to be paper money. The Local Exchange Transaction System (LETS) works by bookkeeping alone. Americans do it on a computer. In Asia and Latin America, pen and paper work just fine. As in the case of the good-for tokens that numismatists know so well, currency can be a wooden coin or anything else that is convenient to carry, easy to identify, and reasonably secure.

Money usually has three attributes. It is a medium of indirect barter. It is a store of value. It is a unit of account. However, money does not need to be all three at once.

One of the interesting attributes of local currencies created since 1920 is that generally, they are not intended to be stores of value. During the Great Depression 300 towns and other entities created a wide array of emergency money, “stamp scrip,” and other media. Back then, one of the expected problems was “hoarding.” The goal of these issues was to encourage spending, to keep money in circulation. Lakewood, Ohio, created scrip that announced on its face and back that it declines in value over time, the dollar of January 1933 being worth 50 cents in June. Other towns relied on other expedients to achieve the same result.

On the other hand, Ithaca Hours, as a “time dollar” is designed to maintain its value. Representing one hour (fractional notes also exist), Ithaca’s notes are relatively stable.

The TACCI committee initially considered a medium that would be independent of the Federal Reserve Note. The original proposal was for a Local Hour, based on a “living wage” of $20 per hour. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides data showing the median factory wage to be about $17 per hour and median family income to be about $50,000 per year for the five county Grand Traverse region.) The intent was to explain to merchants that Bay Bucks should be carried on their books at the preferred tariff of $20 per Bay Hour. However, any business or individual could make whatever choices necessity dictated. A few weeks later, this was deemed too complicated for most people to understand. “One Bay Buck equals One Dollar” summarized the new plan. Consequently, Bay Bucks are tied to the U.S. dollar.

| Board Committees |

| Board Minutes |

| Board Agendas |

| 2021 Spring Activites |

| 2021 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2021 Spring Pictures |

| 2021 Spring Dealers |

| 2020 Fall Activities |

| 2020 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2020 Fall Pictures |

| 2020 Fall Dealers |

| 2020 Spring Activities |

| 2020 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2020 Spring Pictures |

| 2020 Spring Dealers |

| 2019 Fall Activities |

| 2019 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2019 Fall Convention Dealers |

| 2019 Fall Pictures |

| 2019 Spring Activities |

| 2019 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2019 Spring Convention Dealers |

| 2019 Spring Convention Photos |

| 2018 Fall Activities |

| 2018 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2018 Fall Convention Dealers |

| 2018 Fall Convention Photos |

| 2018 Spring Activities |

| 2018 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2018 Spring Convention Dealers |

| 2018 Spring Convention Photos |

| 2017 Fall Activities |

| 2017 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2017 Fall Convention Dealers |

| 2017 Fall Convention Photos |

| 2017 Spring Activities |

| 2017 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2017 Spring Photos |

| 2017 Spring Convention Dealers |

| 2016 Fall Activities |

| 2016 Fall Pictures |

| 2016 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2016 Spring Activities |

| 2016 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2016 Spring Pictures |

| 2015 Fall Activities |

| 2015 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2015 Fall Pictures |

| 2015 Spring Activities |

| 2015 Spring Pictures |

| 2015 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2014 Fall Pictures |

| 2014 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2014 Fall Dealers Attending |

| 2014 Fall Exhibit Winners |

| 2014 Fall Activities |

| 2014 Spring Pictures |

| 2014 Spring Exhibit Winners |

| 2014 Spring Activities |

| 2013 Fall Exhibit Winners |

| Video Rentals |

| Ship and Insure |

| Mayhew Business College Scrip Notes |

| Good For Trade Tokens |

| Tokens of Albion |

| Gale Manufacturing |

| Duck Lake Token Issued By Boat House |

| Albion College |

| New Ira Mayhew College Scrip |

| It Runs in the Family |

| Numis-stability |

| The First “Lincoln Cents” |

| Walking with Liberty |

| Michigan Roll Finds |

| Utica Banknotes |

| Lincolnmania |

| Searching for Rarity and History |

| Numismatics of the 1950's |

| Coining in London and Stuttgart |

| Coining in Paris |

| Coining in Sweden |

| Coining in Japan |

| Coining in Korea |