The Michigan State Numismatic Society

Classicizing America’s Indian in the Mid-Nineteenth Century:

James Longacre’s Indian Cent

Steven Roach

Classicizing America’s Indian in the Mid-Nineteenth Century:

James Longacre’s Indian Cent

Steven Roach

History of Art Honors Thesis Submitted to the University of Michigan History of Art Department

Awarded High Honors, May, 2002

"For both white men and women, fear and fantasy are two sides of the same coin."

Introduction

By the mid-nineteenth century, there were two ways of depicting a Native American. America’s Indian could be presented as a lustful savage that ravaged and held captive honorable white women and children. He could also embody a narrative that recalled a tale of noble, wise, and spiritual keepers of the land. This shift is reflected in many forms of the visual arts, and the new image of the American Indian as a noble savage was a popular subject that could be found in virtually all types of visual culture in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. At mid-century, many artists primarily concerned themselves with romantic and classical depictions of Indians rather than depicting them as savages. By transforming America’s Indian into classically inspired types, artists and the public who viewed their work found an accessible way to make appropriate the subject of the other, while at the same time distancing the Indians depicted from then-current conflicts between Whites and Indians.

Many of the Europeans who settled in North America believed that the key to prosperity was the acquisition of land. Frances K. Pohl writes:

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, and the simultaneous exploration of the northwestern reaches of the continent by Meriweather Lewis and William Clark quickened the pace of westward expansion and demand for land by a rapidly growing population. It also stimulated the interest of artists and writers in this new territory, individuals who, knowingly or not, would help formulate justifications for confiscating the land from its current inhabitants while, at the same time, celebrating the humanity of indigenous peoples, and the value of their cultural practices."

It is this notion of conquest that characterizes America’s relation with the Indian in the nineteenth century. By 1824, the U.S. Secretary of War John C. Calloun declared that Indians were approaching extinction and in 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the legislation for the Indian Removal Bill that relocated 70,000 Indians west of the Mississippi. Thousands died during these forced marches and the survivors were often subject to subsequent removal campaigns to less and less desirable parts of the West. These removals were punctuated by war between settlers and Indians until the late nineteenth century. The Dawes Severalty Act of February 4, 1887 granted the President discretion to allot reservation land to Indians, although this way of life brought the Indians poverty, disease, and hunger. In January 1889, Congress obliged the Creek and Seminole peoples to waive their rights to the Oklahoma Territory and on March 23, 1889 President William Henry Harrison declared Oklahoma open to settlers. Indian life as it had existed a century before had ceased to exist, and by the end of the century, the Indian was a bygone relic of the West and a fatality of America’s growth. At the end of the century, America effectively contained the Indian and was trying to incorporate him into American culture. The rise of the popularity of the classicized, or neutralized Indian distances him from his free past and celebrates his assimilation as a part of The United States of America. It is in this framework of celebration and conquest that these Indian images must be placed into when viewed with modern eyes.

In modern societies, symbolism often involves the public interest and in the nineteenth century, this was concerned with creating defining images for America. Symbolism is often a complex process, and Raymond Firth says that:

"The essence of symbolism lies in the recognition of one thing as standing for another, the relation between them normally being that of concrete to abstract, particular to general. The relation is such that the symbol by itself appears capable of generating and receiving effects otherwise reserved for the object to which it refers – and such effects are often of high emotional charge."

Countries are often symbolized by their products, and what would be a more American product than its native inhabitants? "In the symbol, the relationship between signifier and signified is arbitrary; it requires the active presence of the interpretant to make the satisfying connection." The Indian didn’t have to actually to represent the ideals and character of America, the Indian just had to make a connection as something American to the American public in a time when America was still being re-defined by expansionist policies.

The Indian served as an American symbol in the eighteenth century when the nation was being formed. E. McClung Fleming writes that America’s earliest personification assumed the form of an Indian Queen, representing the Western Hemisphere in the tradition of the Four Continents. He defines the Indian Princess as a separate type from the, "…Very popular Plumed Greek Goddess, a neoclassical transformation of the Indian Princess." Fleming then argues that the first result of the Neoclassic movement popularized by Robert Adam in England and becoming popular in the United States in the late 1780s, was the transformation of the Indian Princess into a Greek goddess. By the nineteenth century the Indian Princess was an antiquated figure. He separates the Indian from the Goddess by her attire:

"The Princess is most clearly Indian when barefooted, scantily dressed in feathered skirt and bonnet, and armed with bow and arrow, tomahawk, or club; the Goddess is most clearly classical when wearing sandals, fully draped in Grecian dress, helmeted or bareheaded, armed with shield and spear or sword. The new symbolic figures however, sometimes constitute an intermediate state when it is often not clear whether the Indian Princess in her feathered headdress has changed into Grecian dress or whether a Greek goddess has put on a feathered headdress."

It is in this transitional space between Indian and Goddess that Longacre’s Indian Head cent fits.

The coin represents just one of the items that an Indian could adorn. The coin itself, by representing a nation through a singular, widely distributed, sculpted image, serves as a form of a public sculpture. Coins are rarely studied as examples of fine art because they are made in such mass qualities and their diminutive size limits their display in museums. Furthermore, the majority of scholarship on coins focuses on their rarity, history, or includes them as evidence in theories of economics. While several scholars discuss coins as art, virtually nothing has been published that places American coins into greater artistic trends contemporary to their production, or that look at coins as cultural objects. Yet, when coins are placed into an art historical framework or used as vehicles of larger social issues, they are extremely valuable lenses to view history with. James Longacre’s Indian Head Cent, conceived in 1857 and first minted for public use in 1859, provides a rich example from which to examine the role of the Indian in visual arts of the mid-to-late nineteenth century and modes of depicting her. Specifically, this four part article will examine Longacre’s Indian maiden and contextualize her through comparisons with other items of visual culture such as public sculpture and advertising of the period. A discussion of the role of the Indian maiden will be compared and contrasted to that of the Indian warrior. The paper will conclude with a discussion of public sculpture and how looking at modern issues in public sculpture impacts one’s reading of Longacre’s Indian and the larger issue of the classicized Indian symbolizing America in nineteenth century art.

The coin represents just one of the items that an Indian could adorn. The coin itself, by representing a nation through a singular, widely distributed, sculpted image, serves as a form of a public sculpture. Coins are rarely studied as examples of fine art because they are made in such mass qualities and their diminutive size limits their display in museums. Furthermore, the majority of scholarship on coins focuses on their rarity, history, or includes them as evidence in theories of economics. While several scholars discuss coins as art, virtually nothing has been published that places American coins into greater artistic trends contemporary to their production, or that look at coins as cultural objects. Yet, when coins are placed into an art historical framework or used as vehicles of larger social issues, they are extremely valuable lenses to view history with. James Longacre’s Indian Head Cent, conceived in 1857 and first minted for public use in 1859, provides a rich example from which to examine the role of the Indian in visual arts of the mid-to-late nineteenth century and modes of depicting her. Specifically, this four part article will examine Longacre’s Indian maiden and contextualize her through comparisons with other items of visual culture such as public sculpture and advertising of the period. A discussion of the role of the Indian maiden will be compared and contrasted to that of the Indian warrior. The paper will conclude with a discussion of public sculpture and how looking at modern issues in public sculpture impacts one’s reading of Longacre’s Indian and the larger issue of the classicized Indian symbolizing America in nineteenth century art.

That the Indian would symbolize national unity in the mid-Nineteenth century and serve as an emblem of Liberty in a period of disintegrating relationship that effectively contained Native Americans and destroyed their culture, poses an interesting question. Furthermore, that the Indian would represent America throughout the Civil War proves that the Indian was a strong unifying image for America. Julie Schimmel suggests that, "White Americans perceived Indians through the assumptions of their own culture. As a result, Indians were seen in terms of what they might become or what they were not, White Christians." The Indian’s use on public art, especially something as widely circulated as a cent, the most common and accessible coin, poses an intriguing question as to how the Indian image is to be read. Furthermore, the representation of Indians within the classical tradition de-contextualizes them from their own history and places them tidily into the framework of Liberty and White America’s history.

Longacre’s Indian Cent

In 1856, one of the United States Mint’s primary focuses was to create a small-sized one-cent coin to replace the unpopular large cents that were circulating. The large cents had a diameter of 27.5 millimeters and a weight of 10.89 grams. The new, smaller cent significantly reduced its size to 19 millimeters and reduced the weight by more than half to a more manageable 4.67 grams. The former cents were designed by Longacre’s predecessor as Chief Engraver of the Mint, Christian Gobrecht, and featured a rather unattractive bust of Liberty facing left. Her hair is styled with thick curls that are contained by a cornet with the text Liberty and adorned with several ropes of pearls. The reverse depicts a simple laurel wreath with the text one cent in the center. The commission to create the designs for the new cent was given to the fourth Chief Engraver of the United States’ Mint, James Barton Longacre (1794-1869) of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. In 1856, approximately 1,500 pattern cents were produced that featured a westbound flying eagle on the obverse and a wreath of American grains on the reverse. The new coins went into mass production in 1857, and while the design seems to have been well accepted by the public, the new copper-nickel alloy was one that the Mint was unfamiliar working with and it caused the Mint to reassess the suitability of the Flying Eagle design. In 1858, the Mint asked Longacre to redesign his cent, the decision to replace it being one primarily of practicality rather than aesthetics.

A single set of dies can produce tens of thousands of coins, and certain designs strike better than others. Longacre was a skilled portraitist best known for his National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans, published between 1834 and 1839. Unfortunately, his skill in engraving portraits was of little use in producing coin dies and Longacre was not able to prepare suitable master dies. In the case of Longacre’s Flying Eagle cent, the coins were frequently produced with softness in the high points of the design including the eagle’s head and wingtips. That the Flying Eagle cent was incapable of being struck correctly in mass-quantities was a combination of two elements. The first was Longacre’s inexperience in the copper-nickel composition that was much harder than the predominantly copper composition used on the large cents. Second, Longacre’s Flying Eagle design utilized a wide field and shallow relief, which lead to cracking in the steel dies that struck the coins. Noting these characteristics, Philadelphia’s Mint Director, James Snowden directed Longacre to prepare new cent designs to replace the Flying Eagle cent as of January 1, 1859.

At Snowden’s request, Longacre produced twelve new pattern coins including four with an "Indian Head" obverse for Snowden’s consideration. After the problems that the Mint had with the Indian Head cent, it would make sense for Longacre to utilize a motif that he had experience with. Longacre first used the profile his designs for the gold dollar and Double Eagle, both minted in 1849. For the Three Dollar coin, first minted in 1854, Longacre modifies his Liberty with a headdress, keeping the same profile first seen in 1849. After some modifications with the tiny dollar coin, Longacre created an appropriate design that proved both popular and efficient. Snowden expressed his preference for the Indian Head obverse in his letter to Secretary Howell Cobb. "The obverse, it will be seen, presents an ideal head of America – the sweeping plumes of the North American Indian giving it the character of North America. It contains the usual legend United States of America with the word Liberty on the headband. The reverse is a plain laurel wreath enclosing the denomination of the coin, one cent." The Indian Head cent was struck in huge quantities until 1909, representing a fantastic 50 year run that came to a halt when the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth ushered in Victor D. Brenner’s Lincoln Cent, the obverse of which is still used on cents produced today. Why would the head of Liberty, dressed up in an Indian’s headdress, seem proper as the ideal head of America and as a symbol of national unity for 50 years?

Exactly who is depicted on Longacre’s Indian Head cent? A story surrounds the origin of the design, although it is now regarded as more myth than reality. Legend has it that the model for the Indian was actually Longacre’s young daughter Sarah, who was sketched while playing with a toy Indian war bonnet. Longacre’s daughter believed the story and shared it on occasion. An elaborate account in a 1906 edition of the American Journal of Numismatics relates the story:

The suggestion of the panache is said to have come from a visit of a delegation of Indians from one of the tribes of the Northwest, who came to talk with the "great Father" in Washington; and while in the East they were taken to see the operations of the Mint. At the time, as the story is told, Miss Sarah Longacre, the daughter of the Mint engraver, was present while the chiefs and their followers were going through the building, and attracted the attention of their leader. In a mood of sportiveness he took his crown of feathers from his head and placed it upon hers. She was a child of five or six years of age, and as she stood for a moment wearing the novel headdress, some of the company made a sketch of the little maiden and her feathery cap, and in due time the design was engraved and used upon the coins, dies for which were then in preparation."

But, as numismatist Walter Breen points out, "Unfortunately for legends and illusions and childhood memories, this identical profile recurs, with many different headdresses, in Longacre’s sketchbooks from 10 years earlier, along with the same adult proportions, always with the same long Greek nose forming in an approximately straight line from tip to forelock." Breen further documents that Longacre referred to this profile in correspondence as patterned after the Greco-Roman Crouching Venus in the collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. That Longacre recycled the profile of Liberty from a classical Venus and adorned her with an Indian’s headdress does not automatically turn her into an Indian. For this to happen, the public has to read the figure of Liberty in a war headdress as an Indian. Ever since the coin had been issued, numismatists and the public have called the coin the Indian Head cent, nomenclature that continues to be used today.

The Indian Head cent was popular when issued and it retains that popularity today. Cornelius Vermeule suggests that this popularity stems from the Indian maiden’s availability. Vermeule writes, "The American public was desperate to trade the classical ideal of Liberty for someone of flesh and blood rather than gilt bronze or marble, and the girlish features of Longacre’s goddess seemed to give them the opportunity." Most likely the desperateness that Vermeule refers to is a comment on the inaccessibility of the stern busts utilized on previous coins, exemplified by the previous large cent. Profiles and design elements on American coinage were typically copied from English and French coins rather than being distinctly of American origin. The opportunity that Vermeule addresses comes at the expense of the ethnographic identity of the Indian. Such an observation poses the question, did the American public care about authenticity and was Longacre conscious of his construction of the popular in his Indian?

That this design was accepted as America is intriguing because Americans at the time were savvy regarding symbols and what they meant. Most likely, the male warrior bonnet would have been read as a headdress worn exclusively by males, so why would the cent, which obviously depicts a woman in a man’s headdress, be so popular? In neutralizing the Indian, many would now read Longacre’s treatment of the subject as trivializing and disrespectful, yet the coin is as popular now as it was when issued. Did authenticity matter in the depiction of the Indian? The longevity of the story, frequently reported today in commercial numismatic publications, suggests the answer to this question is no. Snowden reported that the Indian depicted on the coin was an "…Ideal head of Liberty," and this statement calls into question the role of the Indian image at the time. That a depiction of an Indian, even one as blatantly classicized as Longacre’s, could be considered as an ideal depiction of Liberty and would replace a traditional Liberty, such as Liberty on the large cent, points to the pervasiveness and acceptance of classicizing the Indian image over ethnically descriptive representations. The public’s familiarity with the Indian maiden as an appropriate symbol of Liberty, or as Vermeule puts it, a flesh and bones depiction, points to the lack of concern for ethnographic accuracy in representing America through its native inhabitants and suggests that the approachability of the Indian image came at the expense of its identity. If the figure is completely imaginary and inconsistent, how can Vermeule see this as a flesh and bones depiction? Within the context of the nineteenth century, could this approachability only be achieved via the Indian’s neutralization and through removal of ethnicity and identity? Vermeule reads this neutralization as something that contributes to the cent’s popularity and approachability to both the nineteenth century viewer as well as today’s.

Longacre’s sketchbooks remain preserved in the collections of the Detroit Institute of Arts and several of these drawings have been published by Vermeule. In these sketches, one can see the development of the Indian Head motif out of a classical model. While the profiles that Longacre uses do not deviate from his classical model, his decoration of Liberty is admirable. Vermeule writes, "The one area in which Longacre gave free rein to his imagination was in the matter of fancy headdresses for his renderings of Liberty. His caps of feathers, his bonnets of freedom, and his starry diadems are joys to behold." Longacre’s Liberty has been called an Indian Princess by classic guidebooks, but Vermeule is correct in calling the result, Liberty with Indian attributes. Regarding the popularity and typically American aspect of the coin, he writes:

Far from a major creation aesthetically or iconographically, and far less attractive to the eye than the Peale-Gobrecht flying eagle and its variants, including the small flying eagle turned more toward the viewer, the Indian Head cent was at least to achieve the blessing of popular appeal. The coin became perhaps the most beloved and typically American of any piece great or small in the American series. Great art the coin was not, but it was one of the finest products of the United States mints to achieve the common touch and to identify itself with the transitions from frontier to industrial to social expansion during its decades in circulation, from 1860 to 1930.

Vermeule’s typically American is loaded language for a highly educated and respected curator, but perhaps such words coming from a noted authority prove the authority of the neutralized Indian image and how the notion of the Indian via a headdress can represent America while depicting an actual Indian would be problematic. It cannot be forgotten that a coin that was as widely produced as the Indian cent was not made without careful consideration on the part of Mint and Government officials, each representing separate interests and opinions. A coin is a product of the government that issues it, and represents the ideas and symbols that unify the nation. Longacre’s Indian Head Cent was not the only image of the Indian that the government issued to represent America. Thomas Crawford’s (1813-1857) statue of Freedom atop the dome of the Capitol takes a similar approach to Longacre in creating a symbol of Liberty for a public sculpture. Both artists make a composite image of Liberty that includes an Indian headdress. The story of the politics that went into the construction of Crawford’s sculpture, demonstrates several of the factors that went into the creation of a public American symbol in the mid-nineteenth century.

Crawford, Liberty, and the Capitol

Thomas Crawford’s sculpture for the dome of the Capitol and his interactions with Jefferson Davis (1808-1889) illustrate some of the personal agendas that went into creating public sculptures in the period and are important to consider when evaluating them today. The selection process for the Capitol sculptures has several parallels to the Indian Cent. First, there was a requirement that designs be submitted for approval and secondly, in selecting the themes, national concerns reined higher than the artist’s personal aesthetics. For example, prominent American sculptor Hiram Powers was asked to submit designs for the Capitol, but refused. The reason, was partially because he considered the commission to be an insult after Congress did not purchase his allegorical statue, America. In the case of Longacre, there is little evidence that would indicate that he was unwilling to change his Flying Eagle design, although it was only produced for two years. Rather, in his role as the Chief Engraver, Longacre understood that his prior design was technically inadequate for mass production and in producing multiple pattern cents, Longacre seemed keen on the opportunity to produce another design to replace his own work. While government sculptural projects are primarily dependent on the work of artists without government affiliations, the Mint avoided some of the problems that accompanied commissions such as the Capitol decorations by its reliance on staff artists and engravers to complete designs.

Thomas Crawford’s colossal statue on the dome of the Capitol reflects the iconographic issues plaguing depictions of Liberty at the time and the larger issue of making a singular image for America at a time when the divisions between the northern and southern states were growing stronger each year. While Randolph Rogers, another prominent American sculptor, was first asked to design the statue, he was occupied with a commission of bronze doors for the Rotunda. Crawford was asked to submit designs for the main figure, having worked previously on a Capitol project involving representations of Justice and History on the Senate portico. The Senate project also included an Indian image that will be discussed later; an image produced concurrently with the Capitol dome sculpture.

Jefferson Davis was in charge of the Capitol expansion project between 1853 and 1857. As the Secretary of War, Davis embraced the concept of manifest destiny at the expense of Native Americans. He opposed the usage of the traditional Roman liberty cap that Crawford used in the earlier cornice figures. The cap reflected the Roman tradition where freed slaves would cover their heads with a cap, which for the Romans, stood for emancipation from personal servitude. For early America, this cap was a symbol of America’s freedom from governing nations. Prominent leaders such as Jefferson Davis resisted the cap being depicted with Liberty. Vivian Fryd, who has written extensively on Crawford and his contributions to the Capitol decoration scheme, reported Davis’s thoughts on the cap, expressed in a letter from Montgomery Meigs to Crawford:

"Mr. Davis says that he does not like the cap of Liberty introduced into the composition. That American Liberty is original and not the liberty of the freed slave – that the cap so universally adopted and especially in France during its spasmodic struggles for freedom is desired from the Roman custom of liberating slaves thence called freedmen and allowed to wear the cap."

that the cap so universally adopted and especially in France during its spasmodic struggles for freedom is desired from the Roman custom of liberating slaves thence called freedmen and allowed to wear the cap."

That Davis was a slave owner and future President of the Confederacy makes this notion understandable, especially when coupled with the fact that the public associated the cap with abolitionist representations of Liberty. The cap issue is an example of the problem with classicizing iconography, in this case the cap and its association with freedom from slavery.

In his capacity as the financial and engineering supervisor of the Capitol extinction between 1853 and 1859, Montgomery Meigs, from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, communicated his boss Davis’s opinions to the government and ensured that references to slavery would remain out of the Capitol motif. Meigs wrote to Crawford in May 1855 that, "We have too many Washingtons, we have America on the pediment…Victories and Liberties are rather pagan emblems, nevertheless, Liberty, I fear, is the best we can get. A statue of some kind it must be." The first design that Crawford presented replaces Liberty’s pole and cap with a wreath of wheat sprigs and laurel. Longacre had used this wreath of American grains in several of his previous designs including his Flying Eagle cent. Such wreaths were popular, although aesthetically bland, ways to depict America’s wealth in terms of its agricultural production. Subsequent modifications of Crawford’s Liberty de-emphasized the elements of peace and victory such as the shield and the olive branch in favor of a cap, but Davis condemned the revision with its cap and pole motif. He said, "…History renders it inappropriate to a people who were born free and would not be enslaved…" with regards to inclusion of a cap. Davis suggested that a helmet should replace the cap and that Liberty be armed with chest plating, while retaining her sword. Crawford replaced the cap with, "...A helmet, the crest of which is composed of an Eagle’s head and a bold arrangement of feathers suggested by the costume of our Indian tribes." Davis’s personal agenda to arm Liberty reflects his own militaristic goals, while his acceptance of the inclusion of the Indian headdress into the figure of Liberty attests to the appropriateness of the Indian image within the Capitol Liberty framework that Davis mandated.

The inclusion of a helmet and the subsequent revisions of the sculpture left a final vision that combined three traditional allegories. A traditional Liberty is modified with the war-like attributes of Minerva, and then subjected to further modification by its positioning atop a globe as America. The combination of so many iconographic elements dilutes the power of each singular figure, creating what Fryd calls, a monument that represents a, "Study in compromise and the erosion of a sculptural goal." The feathers that Crawford uses are decorative rather than suggestions of Native American iconography, and yet it is the feathers that give the Statue of Freedom its identity as an Indian.

This brief examination of the problems of iconography on such a large scale is relevant to the earliest American coin designs depicting Liberty. These designs are heavily influenced by the Frenchman Augustin Dupré’s Libertas Americana medal of 1781, where Liberty has flowing hair and depicted behind her is a cap on a staff. American coins occasionally used the cap and pole motif, but in a nation divided on the subject of slavery, Longacre could not have placed a cap on Liberty. Instead, he placed a headdress. Longacre was under similar constraints to those Crawford operated under in terms of having to subscribe to various requirements in the creation of a National image, but clearly Crawford was subject to more personal concerns as represented by the correspondence between Meigs on behalf of Davis and Crawford . Yet, both the Indian Head cent and the Statue of Freedom were popular when they were issued and both retain that popularity today. In looking at public art in nineteenth century America, how Americans interpreted the work is important and often overlooked in favor of arguments of how Americans misunderstood intended symbolism. The general public believed that the Statue of Freedom represented an American Indian princess and more than one congressman identified her to visiting constituents as Pocahontas. The non-specificity of the image of the Indian princess contributed to its warm reception and it supported the nineteenth century desire for sculpture with a narrative. That the statue was read as Pocahontas adds further weight to the image since the story of Pocahontas involves her converting to Christianity and dying in England. Furthermore, she was amongst the most Europeanized Indians, which makes her identification as Liberty understandable as she epitomized the acculturation of Indians into Christianity and white European culture. The American public read Crawford’s and Longacre’s Indian images within the structure of familiar depictions of Liberty. It cannot be forgotten that nineteenth century people were visually literate and the public was well informed about the original meanings of specific classicizing elements, such as the Roman Liberty cap. Armed with this knowledge, any distance that viewers could place between the Indian headdress and the actual Indian would be filled with narrative that familiarized and Americanized the other; that filtered the Indian out of the Indian image. If the purpose of public art is to represent civic virtues and to instill valuable moral lessons, few lessons could be more poignant to a westward expanding America than the domestication of savage Indians through the guidance of settlers and Christianity. Classicizing, essentially Europeanizing the Indian image thus subscribed these depictions to such a philosophy.

Crawford’s The Indian

It is false to think that the American public held a unified view on the role and place of the Indian in the mid-nineteenth century. There were many different conflicting views and to call one dominant would be inappropriate. Fryd mentions an article in The Pioneer that saw, "The Indian in the wilderness as a foe who impedes progress and must, like the forest, be conquered." Others wanted to improve the Indians’ economic position by empowering them through European methods of subsistence such as farming and light industry. Regardless of the methods used, the status of the Indian was quickly changing in the mid-nineteenth century and certain works of art reflect  this change with particular poignancy. No longer was the Indian seen as an eminent threat to America’s manifest destiny, so it was acceptable for artists to appreciate his physical beauty and exploit his nakedness. White artists frequently depicted the naked Indian in part because, the Indian figure could suggest a general aura of romance and sensuality in ways that a depiction of a Caucasian man could not. While to look at the sexual nature as the sole reason for depicting the nude Indian male is tempting, it is also necessary to look at him within the tradition of the classical nude.

this change with particular poignancy. No longer was the Indian seen as an eminent threat to America’s manifest destiny, so it was acceptable for artists to appreciate his physical beauty and exploit his nakedness. White artists frequently depicted the naked Indian in part because, the Indian figure could suggest a general aura of romance and sensuality in ways that a depiction of a Caucasian man could not. While to look at the sexual nature as the sole reason for depicting the nude Indian male is tempting, it is also necessary to look at him within the tradition of the classical nude.

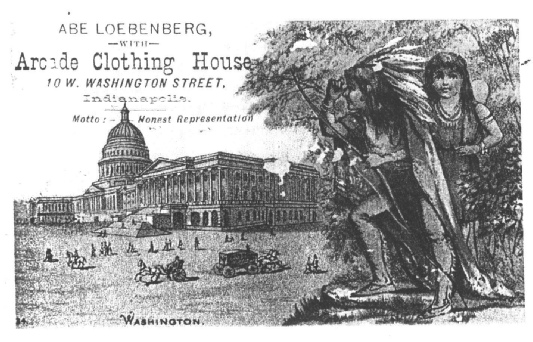

The Indian male is most prone to these depictions as an object of desire, exposed and available, in ways that white men could not be. Thomas Crawford’s The Indian: Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization, exemplifies the sensual Indian male that was popular in American sculpture and painting that serves as a counterpart to the classicized Indian maiden. Sculpted in 1856, Crawford creates a seated muscular chief derived from studio life drawings surrounded by a tomahawk, animal skin, and headdress. Props represent the Indian within the traditional American Indian iconographic tradition. Crawford does not employ a specific Indian, nor does he even use a man with Native features. For The Indian, it is the idea of the once strong figure whose power is removed that is more important than the representation of his actual plight. In the removal of his power, Crawford’s Indian synthesizes both the male and female role in the Indian’s appeal to its viewers. While typifying the view of the Indian as God-like, powerful, and muscular, his posture and resting axe also suggest the female’s role of being subservient and available. Regardless, the Indian’s approachability stems from the idealization of his form and the standard nature of his depiction. In stripping the Indian of his actual identity and replacing it with costume, physical perfection in Western terms replaces the heart, or to use Vermeule’s words, the flesh and blood.

It was acceptable for Indians to be the subject of White desire, their savagery and nobility expressed in their powerful sensuality. Robert Baird writes, "The going-native narrative plays on the fantasy identification of the white man with the free, natural American Indian, who is simultaneously noble and yet able to allow free reign to his wild sexuality." The creation of narrative that stresses the dual nature of the Indian as both noble and wild is important to consider. The body’s perfection embodies the duality that characterizes these Indian images. He is both a natural man, admired as an independent male who resides outside the bounds of civilization while at the same time he is a godless savage in direct contact with the white man’s progress and in direct competition for his women. The Indian’s perfect form gives it reason to be both admired and feared.

Such a sculpture fits into the nineteenth century requirement of a sculpture to have a narrative and indeed, contemporary writers created grand stories surrounding Crawford’s figure. When discussing his sculpture, Crawford himself implicated the Indian’s wife and child in the story, and remarked that his Indian reflected, "All the despair and profound grief resulting from the conviction of the white man’s triumph." The Indian’s seated posture places him within the accessible classical tradition of allegorical female figures of conquered lands that typically show despondent female figures resting in this pose. Longacre’s Indian maiden wears a war headdress that in Native American culture is the hallmark of the heroic male warrior. Crawford’s Indian implies that he is a conquered creature, presented within the tradition of an allegorical female figure of a conquered land.

Such a sculpture fits into the nineteenth century requirement of a sculpture to have a narrative and indeed, contemporary writers created grand stories surrounding Crawford’s figure. When discussing his sculpture, Crawford himself implicated the Indian’s wife and child in the story, and remarked that his Indian reflected, "All the despair and profound grief resulting from the conviction of the white man’s triumph." The Indian’s seated posture places him within the accessible classical tradition of allegorical female figures of conquered lands that typically show despondent female figures resting in this pose. Longacre’s Indian maiden wears a war headdress that in Native American culture is the hallmark of the heroic male warrior. Crawford’s Indian implies that he is a conquered creature, presented within the tradition of an allegorical female figure of a conquered land.

Examining Crawford’s Indian shows how a mid-century American sculptor can address the issue of the removal of the Indian from America in a classical context, and even the most summary look at Longacre’s Indian Cent reveals that Longacre is not at all concerned with presenting an actual Indian. Both Longacre and Crawford share similar concerns. For Longacre, the headdress defines his figure as an Indian and its placement on a coin defines it as Liberty, as nearly all female representations in nineteenth century American numismatics represent Liberty. Longacre’s Indian is not an Indian at all. She is simply a girl in a headdress, appropriating for herself the costume of an Indian; but at the same time, Crawford’s Indian is simply a classical ideal with some accessories that are symbolic of an Indian. Yet, these two figures differ in that Crawford’s can be read to be embedded in American history and Indian removal, while Longacre’s plays the role of an allegorical figure more strongly. The beauty of the sculpted Indians is a nod to the notion of romantic nostalgia rather than accurate ethnographic depiction. That the public viewed Longacre’s cent, along with Crawford’s Statue of Freedom and The Dying Chief as Indians, shows how unimportant authenticity was in depicting Indians to the mass public.

Edmonia Lewis and Minority Identity

Until this point, my discussion has centered on how white men such as Crawford and Longacre, themselves accepted members of the majority, depict the Indian other. How would their sculptures be altered if the artist depicting the other was herself, a minority? To examine this question, one can look at the sculpted works of Edmonia Lewis (c1845-1909). Born in Upstate New York to a Chippewa mother and an African-American father, Lewis is the first documented female American-American sculptor. Encouraged and supported by white abolitionists, she worked primarily in marble and received a traditional training including work in Rome where she focused on depicting contemporary American issues within the framework of Classical precedents. Lewis’ success is notable, for it superceded the prejudices against women sculptors that were strengthened by the physical challenges that are involved when carving marble. Still, while Lewis’ success was noteworthy, it was strongest in circles sympathetic to the abolitionist movement. In her sculptures, she conforms to Victorian gender ideals by presenting her figures in an idealized fashion, sculpting women in the minority, who in their perfection attain a public acceptance that Lewis herself could never achieve.

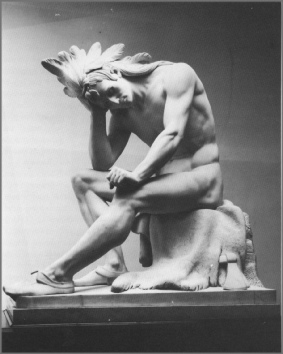

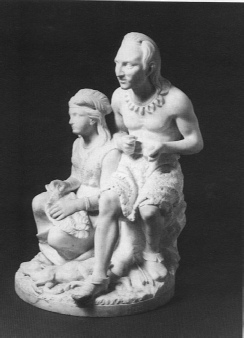

Lewis completed a bust of Minnehaha, an Indian woman from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, in 1868. Flowing hair and a feathered cap accent her soft features, and while her profile is distinctly classical, there is a slight bump in her nose. Yet, this slight bump is the only attempt by Lewis to present her figure within the setting of a specific ethnicity without the use of clothing and props to contextualize her figure and thus, make her identifiable. An examination of the Old Indian Arrowmaker and His Daughter, completed several years later, takes the image of the Indian maiden, and generalizes her even more. Lewis does this by replacing the nose that provided slight ethnographic evidence that Minnehaha was an Indian, with a strictly classical profile, and dresses the daughter in garments that give her the look of a Greek goddess rather than an Indian maiden. While the maiden rests low to the ground, the male figure kneels and asserts his head at a higher position than his daughter. Lewis models the male with the high cheekbones and the hooked nose commonly associated with Indians, while his dress further contributes to the viewer recognizing him as an Indian. This marked contrast between the arrowmaker, and his daughter, illustrates Lewis’ decision to neutralize her women while racializing the men. Lewis worked in a classical style that was easily read by her patrons. She manipulated this vocabulary to provide some distance between her depictions of Indian women and her own life as a member of a minority group.

Yet, Lewis herself did not subscribe to the same ideals that formed the basis for her idealized maidens. She was by all accounts an eccentric, described as mannish, and she never married. Kirsten Buick suggests that Lewis’ mixed racial background contributed to her extreme classicizing of minority female figures since Lewis did not want viewers to make any correlations between her sculpted women and her self, suppressing autobiography so that she could not be read into her sculptures. Regardless, selecting marble as her chosen medium did raise an eyebrow from fellow artists and writers. Henry James described Lewis as, "A negress, whose color, picturesquely contrasted with that of her plastic material, was the pleading agent of her fame." That James would single her out as a negress is interesting in that Lewis’ preferred to emphasize the Native American aspect of her background, and Juanita Holland mentions that the public preferred to note this part of her heritage since she did not easily fit the deeply embedded stereotypical perceptions of African American women. In her talent and intelligence, the public could relate her in the romantic, non-threatening image of the Indian maiden. That her success was a result of her ethnic background rather than her talent strikes a chord with contemporary depictions of the Indian.

Depictions of the Indian were successful for their novelty and identity as the exotic other, rather than for the Indians specific identities, their histories, their character, or their status as the first Americans. Lewis’ maidens have the same appearance as Longacre’s Indian maiden, bearing only the accessories of a specific ethnicity. Identity is found in costume and context rather than actual physical appearance or character. Their classical styling situates them into a framework that the viewer is familiar with, legitimizing both the subject and the artist. While Lewis de-emphasized the features of her African-American and Native American women to distance herself from them in order to achieve objectivity and credibility, Longacre simply used a variation of the classical profile and gave it the paraphernalia of an Indian.

The similarity of Longacre and Lewis’s Indian maidens contrasts with the vastly different backgrounds and interests of the artists. The two artists were extremely different, yet they created remarkably comparable sculpted images. Such sculptural similarities serve to solidify the importance of classicizing the other for mass audiences, yet the differences that separate Longacre and Lewis’ lives, confirm the authority of a classical image in defining identity for both the majority and the minority in the mid-nineteenth century. Lewis’ work was subject to just a segment of the public that Longacre’s work was viewed by. Lewis’ public was primarily abolitionists, a limited audience when compared with Longacre. For Longacre, all Americans, regardless of their political ties, viewed and handled his coins. The Indian on the cent was expected to be read as an Indian by all who viewed it, and this speaks volumes about the power of the Indian image to unify America and exclude minorities.

yet they created remarkably comparable sculpted images. Such sculptural similarities serve to solidify the importance of classicizing the other for mass audiences, yet the differences that separate Longacre and Lewis’ lives, confirm the authority of a classical image in defining identity for both the majority and the minority in the mid-nineteenth century. Lewis’ work was subject to just a segment of the public that Longacre’s work was viewed by. Lewis’ public was primarily abolitionists, a limited audience when compared with Longacre. For Longacre, all Americans, regardless of their political ties, viewed and handled his coins. The Indian on the cent was expected to be read as an Indian by all who viewed it, and this speaks volumes about the power of the Indian image to unify America and exclude minorities.

Reading the Coin as a Public Sculpture

When a government sponsors a public piece of art, it is intended to yield resolution and consensus, not to prolong or promote ideas that are in conflict with national ideals. If the various depictions of Indians in the nineteenth century public sculpture were to accurately depict the actual status of Native Americans, then the sculptures produced would illustrate a series of bloody disputes with unresolved outcomes, rather than a chronicle of heroic accomplishments. Public art, with its built-in social focus, would seem to be an ideal genre for a democracy and one that an emerging America would be quick to exploit, yet in its early days it was viewed as a luxury incompatible with republican values. A reading of a piece of public art must be viewed within the framework through which the work was conceived, commissioned, built, and finally, received.

It is through these criteria that one must examine a design such as the Indian cent and when evaluating a greater phenomenon like the Indian in nineteenth century art. Classicizing was a prominent trend in the nineteenth century, but why did it happen? One reason may be that the technical and conceptual inexperience of American artists and architects required that they look to their training in classical sculpture for answers on how to depict the Native American. As seen in Edmonia Lewis with her depiction of Indians and African Americans, both artists and the public were most comfortable in receiving non-violent depictions of these challenging and new subjects when presented in a familiar, classical, vocabulary. In actuality, if not for the classical image, Indians would most likely be excluded from public art in any role other than the conquered savage.

The classicizing of the American Indian gave artists and the government a way to use the Indian image, and yet avoid any of the actuality that involved the fate of the contemporary Indian. By placing the Indian within the framework of classical forms, the Indian could be noble and anonymous. As such, the Indian could be unthreatening to the national unity that America was forming; a unity that was especially important to depict when one considers the Civil War that followed the creation of Longacre’s Cent and Crawford’s sculptures. That the Native American played a minor role in the Civil War may have played a large part in the popularity of the Indian image as a symbol of America in the mid-nineteenth century. Something that one cannot ignore in looking at the image of the native maiden and noble warrior is the lack of negative stereotypes employed in the art. Unlike depictions of African Americans that are plagued with damaging stereotypes in private art, and generally avoided in public art until the 1870s, the Indian maiden seems generally immune to such harsh treatment. Perhaps part of the reason for this is that America was ideologically divided about the idea of Blacks as slaves, yet the divide was not as strong on the subject Indian removal. But, this reading is appropriate only if one considers figures such as Longacre’s Indian and Crawford’s Statue of Freedom to be Indians. In actuality, these figures are not really Indians at all, just dressed up classical precedents. Still, that such admired forms would represent the Indian, says something about the increased acceptance of the distanced Native American as a figure that was best left to mythology rather than through actual presence.

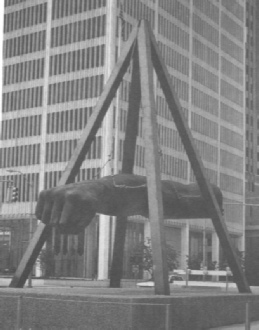

Examining a modern example of public sculpture, Detroit’s Monument to Joe Louis, commissioned by Sports Illustrated seventeen years after the Detroit Race Riots of 1967 helps clarify some of the issues brought up in this paper. In this case, the controversy that surrounded its unveiling in 1986 resulted from, "The inability of the artist and the patron to control the signifier and to define and circumscribe the limits of what was being called to the viewer’s mind." While Joe Louis’ career had been carefully managed to create a public persona of a patriotic family-man, the public reception to Robert Graham’s sculpture could not be so easily controlled. Graham abandons  traditional representational modes of depicting athletes in favor of a 24-foot long forearm with a clenched fist suspended within a 24-foot-high pyramid of four steel beams. The image fit well into Graham’s oeuvre of figural sculpture, but the symbolic rather than literal representation failed to resonate with those who worked downtown and interacted with the sculpture daily. Some observers commented on the sculpture’s resemblance to the clenched-fist black power symbols of the 1960s, while others thought that it failed to depict the range of Louis’ achievements. Still others viewed it as a violent reminder of the riots that had occurred in Detroit just two decades earlier. Regardless, the sculpture, discussed by Donna Graves, represents:

traditional representational modes of depicting athletes in favor of a 24-foot long forearm with a clenched fist suspended within a 24-foot-high pyramid of four steel beams. The image fit well into Graham’s oeuvre of figural sculpture, but the symbolic rather than literal representation failed to resonate with those who worked downtown and interacted with the sculpture daily. Some observers commented on the sculpture’s resemblance to the clenched-fist black power symbols of the 1960s, while others thought that it failed to depict the range of Louis’ achievements. Still others viewed it as a violent reminder of the riots that had occurred in Detroit just two decades earlier. Regardless, the sculpture, discussed by Donna Graves, represents:

"A group traditionally considered peripheral to official history, it recalls elements of a visual language that developed to describe African Americans as the other…by distilling his symbolic tribute to the single image of the punch, Graham ran the risk of recalling the ways in which the lives and legacies of African Americans have been reduced to stereotypes in the public record."

The example illustrates what happens when the artist ignores his audience. Once civic art is placed into the realm of the public, the artists and the governing, issuing bodies, can no longer control the public’s reaction to the final product. This example illustrates in a way that a modern viewer can appreciate, the problems of radical, non-traditional modes of representation. Graham uses a part of Louis, in this case his clenched fist and arm, to represent the whole of Lewis. But when the part that represents the whole is ambiguous, the reason why the person being remembered is depicted is not recalled, and the work loses meaning. In the case of the Indian image in the nineteenth century, seeing these problems makes it more understandable that public art would not stretch convention far in depicting the other. The Graham example clarifies the role of using the male warrior headdress on a female, since America was clear as to the headdress’ association with Indian culture. As the Monument to Joe Louis illustrates, using an unfamiliar visual language to depict the non-majority other brings up issues far beyond the realm of the original commission.

That the public could identify with the Indian head cent was essential to its success and helped the coin achieve a 50-year production span. The cent is America’s smallest denomination coin and was the coin that would circulate among the common people and was be the most widely produced, distributed, and handled coin. A successful public sculpture must be accessible and understandable, and a classical depiction of the Indian on the cent was understood by all who viewed it as Liberty, without any of the problems that would accompany an ethnographically specific rendition that would remind an American of his country’s policies against Native Americans. Crawford was highly aware of the contemporary views of Indians and his appropriation of a headdress lends ease and some authenticity to his Freedom as being specifically American. A headdress is undeniably associated with the Indian who, regardless of the prevailing thought towards its place in society, is seen as the original inhabitant of America’s land. Longacre uses the public’s appreciation for the headdress, if not the Indian, to create a popular design. While I doubt that when Longacre designed the coin he intended it to serve as a vehicle to shape public opinion to favor conquering and disempowering the Native American, the classicized and pacified Indian presents imagery that is embedded with multiple layers of meanings for the modern viewer. By disregarding the actual identity of the Indian, Longacre is able to make a passable Liberty, just as Edmonia Lewis disregarded ethnographic correctness in her sculptures in an attempt to distance her own identity as a minority from those she depicted. Popular advertising images further illustrate the popularity of the Indian image and the true generalized nature of its depiction. . It is in this interchangeability that the classical image of the Indian can be placed. In its classical generalization, the Indian is approachable, familiar, non-threatening, and serves as Liberty with an American edge; American Liberty, depicted as an Indian, without the cumbersome and problematic issue of specific identity.

Images

Thomas Crawford. Statue of Freedom. Atop the dome of the Capitol, Washington D.C. Bronze. 1856-1863. 234 in.

Thomas Crawford. The Indian: Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization. 1856. Marble. 80 x 64 x 40 in.

Unknown Artist. Trade Card. c. 1870. Approximately 4 x 6 in.

Edmonia Lewis. Minnehaha. 1868. Marble. 12 1/8 x 7 ½ x 4 ¾ in.

Edmonia Lewis. Arrowmaker and his Daughter. 1872. Marble. 21 ½ x 13 5/8 x 6 in

Robert Graham. Monument to Joe Lewis. Detroit, Michigan. Bronze. 1986. 24 ft x 24 ft.

Bibliography

Bird, S. Elizabeth. "Savage Desires: The Gendered Construction of the American Indian in Popular Media." In Selling the Indian, Carter Jones Meyer and Diana Royer, ed. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. 2001. 62-98.

Breen, Walter. Walter Breen’s Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. New York: Doubleday. 1988.

Buick, Kirsten P. "The Ideal Works of Edmonia Lewis: Invoking and Inventing Autobiography." American Art. Summer 1995, Volume 9, Number 2. 5-20.

Deloria, Philip Joseph. Playing Indian: Otherness and Authenticity in the Assumption of American Indian Identity. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1998.

Firth, Raymond William. Symbols Public and Private. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1973.

Fleming, E. McClung. "From Indian Princess to Greek Goddess: The American Image, 1783-1815." Winterthur Portfolio III. 1967. 37-67.

Fryd, Vivian. Art & Empire: The Politics of Ethnicity in the United States Capitol, 1815-1860. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1992.

Gerdts, William H. American Neo-Classical Sculpture: The Marble Resurrection. New York, NY: Viking Press. 1973.

Graves, Donna. "Representing the Race: Detroit’s Monument to Joe Lewis." In Critical Issues in Public Art, Harriet F. Senie and Sally Webster, ed. New York: Harper Collins. 1992.

Hawkes, Terence. Structuralism & Semiotics. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1977.

Holland, Juanita Maria. "Mary Edmonia Lewis’ Minnehaha: Gender, Race and the Indian Maid." Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, v. 69.1. 1995. 26-35.

Huhndorf, Shari. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. 2001.

Miller, Lillian B. Patrons and Patriotism: The Encouragement of the Fine Arts in the United States, 1790-1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1966.

Nemerov, Alexander. Frederic Remington & Turn-of-the-Century America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 1995.

Pohl, Frances K. Framing America: A Social History of American Art. New York: Thames & Hudson. 2002.

Pollock, Andrew. United States Patterns and Related Issues. Wolfeboro, NH. Bowers and Merena Galleries. 1994.

Rochette, Edward. The Romance of Coin Collecting. Wolfeboro, NH: Bowers and Merena Galleries. 1991.

Savage, Kirk. Standing Soldiers: Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 1997.

Schimmel, Julie. "Inventing The Indian." In The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1991. 149-189.

Steele, Jeffrey. "Reduced to Images: American Indians in Nineteenth-Century Advertising." in Dressing in Feathers, Elisabeth Bird, ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 1996. 45-62.

Truettner, William H. The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1991.

Vermeule, Cornelius. Numismatic Art in America: Aesthetics of the United States Coinage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1971.

| Board Committees |

| Board Minutes |

| Board Agendas |

| 2021 Spring Activites |

| 2021 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2021 Spring Pictures |

| 2021 Spring Dealers |

| 2020 Fall Activities |

| 2020 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2020 Fall Pictures |

| 2020 Fall Dealers |

| 2020 Spring Activities |

| 2020 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2020 Spring Pictures |

| 2020 Spring Dealers |

| 2019 Fall Activities |

| 2019 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2019 Fall Convention Dealers |

| 2019 Fall Pictures |

| 2019 Spring Activities |

| 2019 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2019 Spring Convention Dealers |

| 2019 Spring Convention Photos |

| 2018 Fall Activities |

| 2018 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2018 Fall Convention Dealers |

| 2018 Fall Convention Photos |

| 2018 Spring Activities |

| 2018 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2018 Spring Convention Dealers |

| 2018 Spring Convention Photos |

| 2017 Fall Activities |

| 2017 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2017 Fall Convention Dealers |

| 2017 Fall Convention Photos |

| 2017 Spring Activities |

| 2017 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2017 Spring Photos |

| 2017 Spring Convention Dealers |

| 2016 Fall Activities |

| 2016 Fall Pictures |

| 2016 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2016 Spring Activities |

| 2016 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2016 Spring Pictures |

| 2015 Fall Activities |

| 2015 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2015 Fall Pictures |

| 2015 Spring Activities |

| 2015 Spring Pictures |

| 2015 Spring Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2014 Fall Pictures |

| 2014 Fall Exhibit Sponsors |

| 2014 Fall Dealers Attending |

| 2014 Fall Exhibit Winners |

| 2014 Fall Activities |

| 2014 Spring Pictures |

| 2014 Spring Exhibit Winners |

| 2014 Spring Activities |

| 2013 Fall Exhibit Winners |

| Video Rentals |

| Ship and Insure |

| Mayhew Business College Scrip Notes |

| Good For Trade Tokens |

| Tokens of Albion |

| Gale Manufacturing |

| Duck Lake Token Issued By Boat House |

| Albion College |

| New Ira Mayhew College Scrip |

| It Runs in the Family |

| Numis-stability |

| The First “Lincoln Cents” |

| Walking with Liberty |

| Michigan Roll Finds |

| Utica Banknotes |

| Lincolnmania |

| Searching for Rarity and History |

| Numismatics of the 1950's |

| Coining in London and Stuttgart |

| Coining in Paris |

| Coining in Sweden |

| Coining in Japan |

| Coining in Korea |